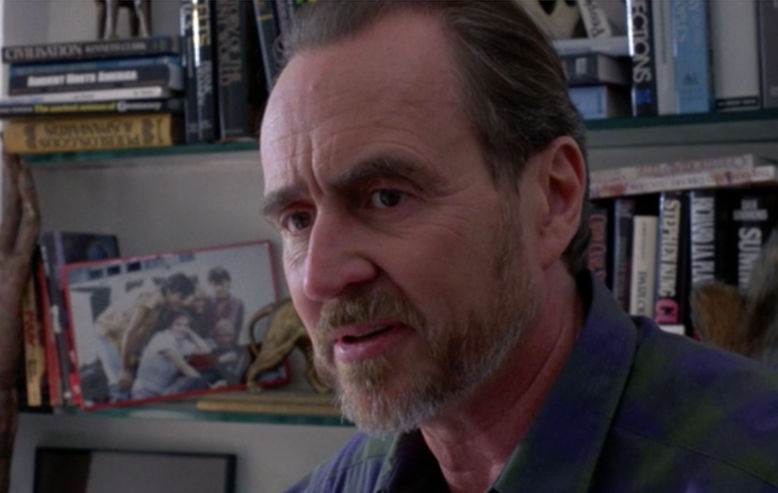

Most people in the horror community have been mourning the death of Wes Craven. Now that his oeuvre is (sadly) complete, it’s amazing to look over his filmography and see how many legitimately great films he made over more than four decades. As fans know, Craven began his career as a Professor with a Master’s Degree in English and Philosophy. He left this path to pursue his passion for filmmaking. Craven had such a knack for making game-changing horror films that he became eternally associated with the genre. However, he never lost the love for philosophy, literary themes, and social justice that first inspired him to become an academic. Few directors have so excelled at making overtly political, intellectual horror films that also managed to be incredibly popular, entertaining and scary. So today, I celebrate not just how Craven gave us nightmares, but how he taught us about being human. He was a master of horror, but I come to praise him as a philosopher.

Please note: some of the following analyses may contain spoilers.The Last House on the Left (1972)

What it’s about: Mari and Phyllis leave the placid suburbs to attend a Bloodlust concert in New York’s East Village, circa 1972. An innocent quest for marijuana leads to their kidnapping by a gang of vicious serial killers. In a crazy coincidence, the killers’ car breaks down in front of the woods outside Mari’s house, where they torture, rape and kill the girls. Afterwards, they seek shelter with Mari’s parents, who discover what they’ve done and exact bloody revenge.

What it has to say: People, all people, are complicated.

The first time I saw The Last House on the Left, at an unspeakably young age, I felt like I had stared pure evil in the face for the first time (and this was longafter I fell in love with Freddy Krueger). I have nightmares about it to this day. I couldn’t bring myself to watch it again until college, and at that point it made me confront something even more terrifying: its villains — who I still believe to be the scariest villains in any movie, ever — are human. Many have cited the chilling scene, after Krug shoots Mari, in which Krug, Sadie and Weasel look at each other with a note of guilt, regret, and maybe even sadness. In Robin Wood’s brilliant analysis of the film in the book Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan, he also points out the class tensions that rise to the surface when the gang takes shelter in the house of Mari’s wealthy parents. The criminals naively demonstrate bad table manners during dinner and, when alone, angrily discuss how Mari’s upper middle class lifestyle was so much more comfortable than theirs. Craven insists on showing how America’s class divide contributes to their terrifying anger, making it even more impossible to leave the movie feeling comfortable about our world.

Swamp Thing (1982)

What it’s about: Dr. Alec Holland creates a serum that will strengthen local plant-life, allowing the local flora, fauna, and wildlife to thrive. A bunch of thugs try to steal his concoction for financial gain, and try to kill him with an explosion that throws him into the surrounding swamp. He returns as Swamp Thing, eager to avenge his assault and save Adrienne Barbeau, the love of his and everybody else’s lives.

What it has to say: People will try to commodify nature. It will lead to their destruction.

Craven comes back to this message again and again. In The Serpent and the Rainbow, Bill Pullman tries to turn voodoo powder into a marketable pharmaceutical. He ends up buried alive with a tarantula. That family in The Hills Have Eyes would have been fine if they’d just gotten to Los Angeles without stopping to forage for silver in the mountains. For now, though, let’s focus on lovely Swamp Thing. Swamp Thing is an actual physical manifestation of nature’s revenge on those who exploit it. In these days of drought, global warming, and natural disasters, we feel his presence everywhere.

Invitation to Hell (1984)

What it’s about: A nice, boring family moves to a quintessential ‘80s California suburb so that dad can work at the tech start-up Microdigitech (tech start-ups are always evil). The wicked Jessica Jones (Susan Lucci!) insists that they join her chic local health club, which is basically the same thing as donating their souls to Satan.

What it has to say: The rich and powerful will tempt those beneath them with material goods in order to distract from the fact that they are evil.

We immediately know that Jessica Jones is evil incarnate because she gives Joanna Cassidy a trendy, shoulder-padded makeover and turns her house’s décor motif from “E.T. cozy” to “Dynasty severe.” Lots of leather couches, track lighting, and a giant black shellacked vase signify the presence of dark forces. Mom’s new devotion to wealth and image starts having a palpable effect on the family, and eventually dad is dangling off a cliff with his feet tickled by the fires of hell. I think Wes would have agreed that the most powerful of the 1% will do anything to distract the 99% from the fact that they do not have their best interests at heart, including making them think that buying a lot of tacky furniture will bring them happiness.

I am not highlighting The People Under the Stairs here because I wrote about it in my last post. However, I have to note that it adds nuance and potency to Craven’s “Eat the Rich” message. That film’s chilling villains, Man and Woman, forcefully demonstrate that capitalist greed, racism, paranoia and violence against the innocent are four sides of the same puzzle box. Both films are more relevant today than ever.

Deadly Blessing (1981)

What it’s about: After her husband dies in a freak tractor accident, a woman invites her spunky girlfriends from Los Angeles (including Sharon Stone!) to come and comfort her. The Hittites, a local, fanatical religious sect, led by crazy Ernest Borgnine, don’t like these women and their feminist succubus ways. Scary sh*t happens to them.

What it has to say: Organized religion can easily lead to hypocrisy, oppression and violence.

When Craven was young, his mother belonged to a fundamentalist Baptist church that took the Bible literally. They proclaimed that anybody who didn’t follow their interpretation of its word would burn in the fires of hell, which made things tough for the agnostic Craven (for more about this, check out John Wooley’s Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares). Most of his work demonstrates a comfort with the notion of spirituality, but criticism of the ways in which people get together and use religion to oppress others. This criticism manifests itself most overtly in the plot of Deadly Blessing, in which a religious leader seems to lead his followers to commit everything from lawnmower homicide to feeding Sharon Stone tarantulas in her dreams. SPOILER: The film’s finale reveals that the purpose of all of this oppression has been to hide the unconventional gender orientation of one of the sect’s members. Why can’t we all just accept each other?! Admittedly, this movie’s “twist ending,” tacked on by the studios against Craven’s wishes, renders its messages contradictory and semi-incomprehensible. But Wes makes his ambivalence towards religious groupthink pretty clear.

Scream (1996)

What it’s about: A killer stalks Sidney and her friends, forcing them to fatally re-enact his (or her’s? Or their?) favorite scary movies.

What it has to say: If people allow themselves to learn from their experiences, their most profound struggles will ultimately be their salvation.

Sidney has undergone one of the most severe traumas imaginable: She watched her mother get killed. Her post-traumatic stress symptoms (a hyper attunement to her surroundings; a lack of trust in the safety of everyday life), and the self-defense strategies that she develops in response to them, ultimately allow her to save herself from the killers. In Scream 4, she again makes lemonade from some seriously sour lemons by turning her devastating teen years into a bestselling self help book! Sidney is a constant source of inspiration, truly.

Shocker (1989)

What it’s about: After his execution by electric chair, a serial killer comes back from the dead to murder Jonathan, the football hero who got him caught. Oh, also, he and Jonathan are weirdly psychically connected by dreams and cable television.

What it has to say: Loved ones make each other strong.

We love Shocker, but it’s totally insane. Killer Horace Pinker spends the second half of the movie possessing everybody from policemen to cute little girls, and then he and Jonathan get sucked into a satellite dish and have to chase each other through cable channels. Given that the movie is literally filled with mayhem, it seems especially bizarre that Jonathan’s relationship with his girlfriend Alison is legitimately moving and effective. Even after she dies, she comes back as a spiritual guide to advise him and protect him. The necklace that he gave her to celebrate her birthday is the only talisman that can truly fight off Horace Pinker. Craven’s early films were incredibly cynical about the notion of family. Even nice families like the Collingwoods in Last House on the Leftharbored a tremendous capacity for violence, and the parents in A Nightmare on Elm Street were beyond useless. However, his later films were a bit softer in this regard, emphasizing people’s ability to take care of each other rather than the all-importance of self-reliance. Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares cites an interview in which he states “the real foundation of strength is the family and the support you can give each other.” Craven’s latter movies, perhaps beginning with Shocker, are notable for demonstrating that sometimes the most important families are not those to which we were born, but the ones that we find and create ourselves. Perhaps most movingly, in Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, the semi-fictional version of Heather Langenkamp seeks solace and support in her “self-made” family of Wes Craven, Robert Englund, and John Saxon, after Freddy kills her husband and comes after her.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

What it’s about: Do I really need to tell you? A burned man with knives for fingers stalks Nancy and her friends in their dreams. It turns out that he’s the ghost of a child murderer whom their parents hunted down and killed.

What it has to say: In order to conquer your deepest problems, you must confront them.

Towards the end of A Nightmare on Elm Street, Nancy’s mother gives her some typically terrible advice: “You face things, that’s your nature. But sometimes, you have to look away.” This attitude, taken by the majority of people in our society who are confronted with ordinary violence, allows people like Freddy Krueger to thrive. Nancy knows that it won’t fly. Yes, she turns away from Freddy at the end of the film. But even though she does not face him physically, she confronts him nonetheless. In the moment in which Nancy says “I take back every bit of energy I ever gave you. You’re nothing. You’re sh*#,” Nancy faces Freddy for what he really is for the first time, and in doing so takes away all of his power. In life, many personal demons can be conquered the same way. Most of the Nightmare on Elm Street sequels are very close to my heart, but I absolutely understand why Craven was furious at New Line head Robert Shaye’s insistence on tacking on a cheesy shock ending where Freddy returns. It totally violates the enormous power and wisdom of Nancy’s final exchange with Freddy. So I just like to pretend that it ends as Craven originally intended, with Nancy walking off into the sunlight.

Wes Craven’s New Nightmare

What it’s about: Right as the original Nightmare‘s cast and crew gear up to make a new entry in the series, the original, scary as hell, non-wisecracking Freddy comes into the real world to punish them for making him into a commercialized joke.

What it has to say: You can go home again, and sometimes you must.

The massive success of A Nightmare on Elm Street was a mixed blessing for its makers. It gave Heather Langenkamp a stalker, but mysteriously didn’t lead to many additional roles. Craven got more or less pigeonholed into making horror films almost all the time, to his regret (let me take this moment to say that I love Music of the Heart), and he disliked where the series went after his original. Much like Nancy in the original Nightmare, Craven decided to face his demons by making a surprisingly frank horror movie about some of the negative results of Freddy Krueger’s super-stardom. At the film’s climax, Craven tells Nancy that the only way to evict Freddy is for her to go back into the world of the Nightmare on Elm Street movies and play Nancy one last time (a scene that, I won’t lie, brought me to tears when I saw the movie in theaters). Some people have posited that Wes Craven sees himself as Freddy Krueger, since Freddy Krueger is “the author” of teenagers’ nightmares. I couldn’t possibly disagree with this theory more, and it goes against everything that Craven has ever said in interviews. I suspect that Craven has always identified with Nancy and Heather Langenkamp (after all, he insisted on bringing both of them back in each of the Nightmare movies that he wrote and/or directed). When Langenkamp goes into movie-land and finds herself wearing Nancy’s old pajamas and staring up at Nancy’s iconic house, looming larger than ever before, one senses that Craven is also coming to terms with his looming past. Sometimes you must first come to terms with where you have come from to get where you need to go. Two years later, after 20 years of being (wrongfully) defined in the mainstream as “the guy who created Freddy,” Craven helped reinvent the genre again with Scream.

Craven’s Entire Body of Work

What it has to say: Darkness lurks constantly beneath the “normality” of our society. Those who try to deny it allow it to thrive. Those who show it and talk about it fight against it.

Throughout his career, Craven’s movies were criticized for inciting violence. In all fairness, there were several cases in which people with untreated mental illnesses committed crimes based on imagery in his films, but I would argue that the untreated mental illnesses were the bigger problem. Many authority figures assumed that kids who liked violent movies would become dangers to society. I’ve met a lot of people who were persecuted for their love of Wes Craven’s movies as kids, and I experienced some of this stigma from adults in my hometown (although not, thankfully, from my own parents).

My dissertation research deals with the ways in which people use their love of popular culture to process experiences of trauma. While conducting research for it, I encountered a lot of Wes Craven fans. None of them would ever commit violence. Many of them loved his movies because they helped them to deal with actual violence that was perpetrated upon them (such as abuse, neglect, and bullying). In several cases, these people found that the same adults who were concerned about the effects of violent movies on kids “looked away” from their suffering, like Nancy’s mother tried to look away from the return of Krueger. Wes Craven knew that, very often, real violence — at least in the suburban communities that he most frequently represented — did not happen because horror movies showed it, but because most people didn’t want to deal with the fact of its existence. Craven never looked away, and he encouraged those who loved his work not to look away either. A meme that circulated on the day of Craven’s death quoted him as saying “Horror films don’t create fear. They release it.” Wes Craven’s films did not only release our fear. For many, they gave very necessary tools to overcome fears and dangers generated not by movies, but by reality. I know that I am one of many who was deeply touched, changed and guided by his work. We will always be grateful.

Ben Raphael Sher is VP of Development at XG Productions. He holds a PhD in Film, Television, and Digital Media from UCLA, where he teaches. He also writes for Chiller TV (http://www.chillertv.com/friday13), SyFy (www.syfy.com), and his blog, Eyes of Ben Sher (http://eyesofbensher.blogspot.com). He is a regular co-host of the Retro Movie Love podcast (http://retromovielove.com).