This essay, by Adam Gopnik, can be found in Steve Martin: The Television Stuff

There is, everyone says, no explaining comedy. And it’s true. Funny evades explanation as much as sexy does, and for the same reasons. Their causes may be subtly orchestrated, but their effects are entirely clear: having to say why something is funny or sexy means that it’s not. The too-well-explained old joke becomes the cause for the pained “mirthful” forced laughter that fills the theater at Ben Jonson comedies, and even sometimes at Shakespearean ones.

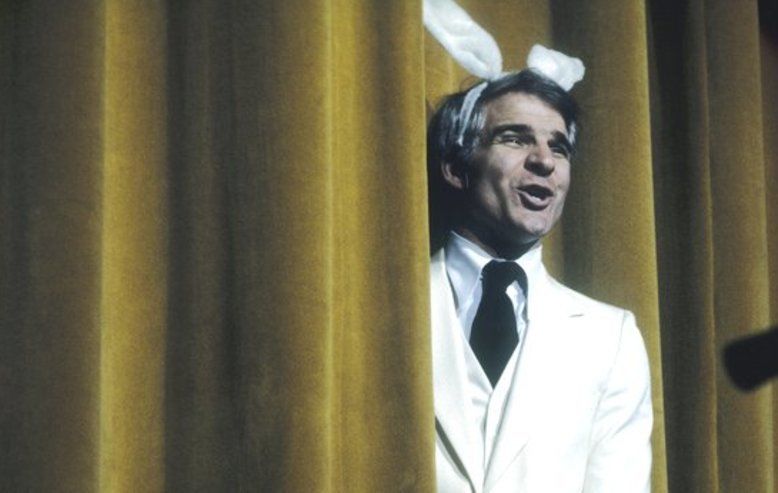

But though there’s no point in us trying to explain comedy, there is a way of figuring out why comedy explains us. Watching what this boxed set contains, which is mostly material from Steve Martin’s television specials and concerts from the 1970s, highlights of what we might now call Early Steve — with an eye to the other, sometimes darker Steve Martins that have emerged since — a whole sweet period in the history of American laughter comes back to life. Has there ever been anything more improbable than the rage, the mania, for Early Martin, the banjo-playing balloon-animal-maker man in the white suit, the wild and crazy guy — which filled stadiums in the late ’70s? As the concerts documented and preserved on these DVDs display, what had been an eccentric nightclub act filling the Troubadour (at five dollars a shot) became, in relatively short order, a stadium act, stuffing the same arenas where only Spinal Tap-ish rock bands were thriving in the same period.

What made it happen? Martin himself has brooded on it, in his fine, honest memoir Born Standing Up, revealing that it grew more slowly, and was more carefully deliberated, than one might think. Seen from a distance, and from the slightly more detached perspective of someone watching then and who is watching now, you also see it was the power of a period, a wave of good feeling, now forgotten, that swept the country in the much-misunderstood ’70s that helped make that moment happen . . . but mostly it was the sublime absurdity of a comedian who, putting all else aside, dared to be silly.

Seeing mint Martin from the mid-’70s, it is startling all over again to see what a sublimely, exclusively silly attitude he struck. The act, the man in the white suit (though here, earlier on, he just wears gray) surfs, even more resolutely than one had recalled, the up and down waves of phony performer’s emotion. “Professional show business” is the promise he smugly offers at the beginning of his act, and Steve, the character, really has mastered all the outward signs of pro show biz as it was practiced at the time. There are the intimate confidences offered close into the microphone (“I get my drinks here . . . half price,” with those matchlessly expressive eyebrows implying the self-congratulatory ellipsis); the smooth transitions between one “skill” and another (“I suppose you’ve heard that I’m into the . . . comedy thing. Sort of getting more into the music thing . . . ”); and the sheer, sweaty exhaustion of a performer who just, damnit, can’t help but give too much.

That the character offering this assured performance, these confident intimacies, is in truth the most ill-equipped and hapless entertainer in the history of the stage, is the first source of the comedy. It is the immense pleasure, the pride, he takes in his own cluelessness, even more than any pleasure the audience takes in him, that makes the show still giddily funny. Even as he ambles aimlessly from bit to bit, displaying his nonexistent (or completely irrelevant) skills as a card sharp, magician, balloon animal-maker, he thinks his act is a smash. Houdini at the height of his powers was not more self-assured. He thinks he’s great, and his self-confidence becomes contagious — we think then that he is great, in his own self-made way. The character Steve inhabited is a sort of divine fool of stand-up, an innocent of show business: his not getting it is what makes him get it. (Andy Kaufman would take the same type, the performer whose only experience is the clichés of performing, and find a more sinister hidden edge within the character that some found sublime, others just creepy.)

All comedy depends on shared social expectations. It’s a two-way street, with signals sent and gratefully received; and, despite an absence of topical humor, the comedy of early Steve is entirely generational. He depended on his audience knowing the clichés of Vegas and nightclubs by heart — though they took that knowingness from television, which had made the Vegas nightclub manner commonplace. Steve was working for perhaps the first generation whose experience of entertainment was almost entirely the experience of talk shows and variety shows, which is where the Vegas entertainers went to do their acts. (And they did them, perhaps not coincidentally, in a more rushed form for Merv Griffin or Johnny Carson than they did onstage; Steve’s super-rushed versions of the same act are in some ways parodies of an abridgement.) Comedy often works by pointing without embarrassment to some cultural piety that has died and that no one has been quite willing to admit is dead — the Marx Brothers get a lot of mileage just from knowing that grand gestures of the opera were, by 1940, ridiculous in themselves. By the early ’70s, the clichés of 1950s Rat Pack show biz, which had to an earlier generation seemed quite organic, thrilling in their spontaneity, had been shipwrecked on the shores of summer replacement variety shows.

Around the same time, or a few years earlier, George Carlin had made a similar revolt against the mannered clichés of television and show business, but he had based his comedy on hipness — to other kinds of in-group references, those of the drug and “counterculture,” which had previously been ignored. Steve Martin, coming from a similar kind of television background, didn’t turn to hipness but to anti-hipness, creating a character so out of it that his out-of-it-ness became another kind of hip — the meta-hip of the knowing rather than the moralizing hip of the satirical-minded. He was showing a hip audience what absolute unhipness was like, and how much fun it might be. He was pretending, as Pauline Kael remarked, to be a comedian, loyal to show biz rituals, while his audience pretended to be an audience, receptive to them.

There was also, in the absence of obvious topical “thrust” in Steve’s early comedy, an implicit kind of social truce, also typical of the 1970s. “I knew that the war was over,” is how Martin puts it today, simply — meaning not just that the war in Vietnam was over (though it was), but more broadly that the conflicts between generations had mostly ended, with, as always happens, the younger generation routing the old. Lorne Michaels, the producer of Saturday Night Live and one of Steve’s key supporters in this period, says that his program flourished, in part, “because the pillars of society were discredited — post-Watergate, you couldn’t trust the government or the press — but also because we were just the first young people to have a television. We came on and no one could object to what we were doing, because everyone had learned that they couldn’t trust anything.” The triumph of what had seemed an embattled countercultural idea of comedy meant that certain permissions were also given. “Richard Pryor and Lily Tomlin had been doing self-consciously important work. Steve, when he showed up in the white suit, arrow in the head, making balloon animals —it was just silly and had the nerve to be silly,” Michaels adds.

So there is both mockery and a kind of affectionate salute to worn-out show business mannerisms in Steve’s comedy. The show biz affectation of sincerity is his favorite subject. “We’ve had some fun out here, and I think it’s so important to do that,” he announces in a confidential tone, eyes half-shut, toward the end of his act, in just the manner of a Sammy or a Dean or even a Frank after they had finished the wild, daring part of their performance and wanted to close out with something a little deeper, a little more misty-eyed. “Not trying to get corny with you or anything . . . ” he then murmurs, matchlessly corny, and the eyebrows and the modest tilt of the head are so expertly worked that they almost mislead one, still today, into thinking that something straight might be about to happen. “A day without sunshine is like